Hog Life

When a grown man pays a pile of money to act like a little boy, people call it a mid-life crisis. In my first half-century of life, I’ve had four. The first two were sports cars. The last two? Motorcycles. This is the story of my motorcycles.

I spent the summer of 2013 training to run my first marathon. Most mornings, long before the world awakened, I’d strap on Sauconies and jog for miles. I’d return home sloshed in sweat, my shoes squishing at every step. I’d wear out a pair of shoes in two or three months. My weight dipped below 200 pounds for the first time in two decades. I felt great and fit and decided that I’d mark my first marathon by learning to ride a motorcycle. I signed up for a learn-to-ride class scheduled for a week after the marathon.

Why a motorcycle? I could pretend it was for practical reasons: better gas mileage, less garage space, smaller environmental impact, and lower wear and tear on the roads. But that fools no one. Motorcycles are the anti-practical. You can’t take your family with you. You can’t comfortably commute on a motorcycle in a business suit. You can’t ride in a storm without bagging up in rain gear. You can’t go grocery shopping for more than a garlic clove and a box of Tic Tacs. And they’re hopelessly dangerous. The allure of motorcycles runs deep, however: the open air, the growl of the engine, and the devil-may-care freedom. Renegades have long ridden motorcycles, from James Dean’s Rebel Without a Cause to Henry Winkler’s “The Fonz” to Evel Knievel’s bone-breaking jumps. Riding a motorcycle also summons the inner child, reaching back to when you hopped on your Huffy with baseball cards in the spokes and pedaled to a friend’s house whose mother left the cookie jar unguarded, or to the ball field to play catch, or to a creek to catch minnows and tadpoles, unreachable and unfettered for the day. Of course I knew the dangers, but the growl of the engine muffled worry and practicality.

The marathon came, I crossed the finish line with arms outstretched and legs quivering, and then prepared for the motorcycle class. The brochure explained that they provided both motorcycle and helmet to all students. I figured I’d ride their motorcycle, but no way was I wearing their helmet. The thought of stuffing my head into padding stained by strangers’ sweat disgusted me. A few days before the class began, I drove to my local motorcycle shop and bought my own helmet. Motorcycle helmets come in various styles, from “Brain Bucket,” which teeters atop your crown like you’re about to get a bowl cut at the barber shop, to “Full Face,” which erects a fortress around your entire head. As a husband and father of five, I bowed to safety and bought a Full Face helmet. When I jammed my new helmet on my head and yanked down the face shield, I felt I could fight dragons. I didn’t buy some budget brand, either; I bought a Shoei. If you don’t know your motorcycle helmet brands, Shoei leads the pack. I cut no corners. I’d be well-protected. I wore my Shoei to my two-day class, learned how to ride responsibly, and got my motorcycle license.

I bought my first motorcycle, a used black Honda Shadow with a 750cc engine, on eBay. I paid about $3000. The seller drove it to my house and said, “My wife is so happy I’m selling this.” Someday, when my life flashes before my eyes, I’ll hear ominous music during that scene. Oblivious to foreshadowing, though, I forked over a cashier’s check, threw my leg over the seat, and eased my new bike over the curb at the end of my driveway. My oldest son, watching out the window, later said I rode “like a little bitch,” but time and practice diluted my caution. I learned how to ride in traffic, how to cancel my blinker after turning, and how to zoom from my driveway. I learned the biker’s wave: a sort of downward salute where you point with your left hand diagonally at the ground as you pass another rider. I learned about the responsible rider’s mantra — ATGATT, pronounced “at gat,” which stands for “all the gear, all the time” — and geared up for every ride. Helmet. Gloves. Long pants. Jacket. I started with a reasonably-priced yet durable mesh jacket. Even the breathable mesh proved suffocating by late spring in Florida, though, so I bought another, thinner mesh jacket. By summer, though, stoplights or stop-and-go traffic left me in sweat baths, even with the lighter jacket, so I shed all jackets until fall. I figured MOTGPMATT — “most of the gear, pretty much all the time” — was at least better than the helmet-less riders I so often saw. I’d even see riders in tank tops, board shorts, and flip-flops. I was never so irresponsible. “Reasonably responsible,” or RR, was good enough for me.

You learn as a motorcycle owner that everyone knows someone who was killed or maimed on a motorcycle. And when they learn that you ride, they can’t help it; they have to tell you about their friend/family member/neighbor and their accidents. First they suck in a deep breath, mouth forming a disapproving “O,” and then they shake their heads slightly as they recount the story. Breathe. Shake. “I had a friend who rode. A soccer mom with a venti latte ran him into a telephone pole. Said she never saw him. One arm stayed embedded in the pole, and his head got tangled in the wires. Flew clean off.” Then they look at you, expectant, as if you’re going swear to list your bike on Craigslist that very afternoon. I learned to don a grave expression, shake my head in what I hoped was perfect mimicry, and say, “Wow. Crazy. That’s terrible.” And then move on. Because, as sad as the stories were, those were other people’s problems. Wrecking my bike was never going to happen to me. I’d stay alert. I’d anticipate other drivers’ myopia. I’d ride safely. So when my father-in-law, an undertaker, would tell me about yet another rider’s body he’d picked up, I’d shake my head and say, “Wow. Crazy. That’s terrible.” Cue the ominous music.

A year and 3,000 miles later, I’d outgrown my Honda Shadow. My small investment had proved that I loved to ride and wanted to keep riding. Now I wanted a bigger, meaner bike. I wanted to elevate my fraternity. I wanted a Harley. I traded my 750cc Honda Shadow for a 103ci — that’s about 1,690cc — brand new, 2015 Harley-Davidson Street Bob. It came with mini-ape handlebars, a saddle-like solo seat, and a custom factory paint job: matte black with silver swirls and skulls. The paint job was one-of-two on the entire US East coast. It was bigger, badder, tougher, and faster than the Honda Shadow. On the protests of my children, I later added a removable rear seat and detachable saddle bags — nods to practicality that I jettisoned when cruising around by myself. Harley enrolled me in the official Harley Owners Group, and I grew out my beard halfway to Duck Dynasty. I bought a few Harley Davidson t-shirts and longed for a Harley Davidson leather jacket, but the $600 price tag slowed me down. Still, now I rolled with the Hogs.

Early in our marriage, my wife would see a couple sharing a motorcycle and swoon. He’d be driving, back straight, shoulders broad as his handlebars and chin square like a box wrench. She’d straddle the seat behind him, wrapped around him like a feather boa, green lights reflecting off her eyes. “Let’s get a motorcycle and ride together someday,” my wife would purr, and I’d pant that yes, we would. After buying my motorcycle, I looked to cash in and leered. “Let’s go for a ride,” I said. Frost and fear fell over her. “No way!” she said. “It’s too dangerous.” Years of raising children had lowered her mettle (and perhaps libido). We tried it once when we had to pick up her pickup from the shop, and she clung to me out of panic, not passion, yelping, “Oh shit!” In my ear the whole ride. I abandoned any plans for midnight rides in the moonlight.

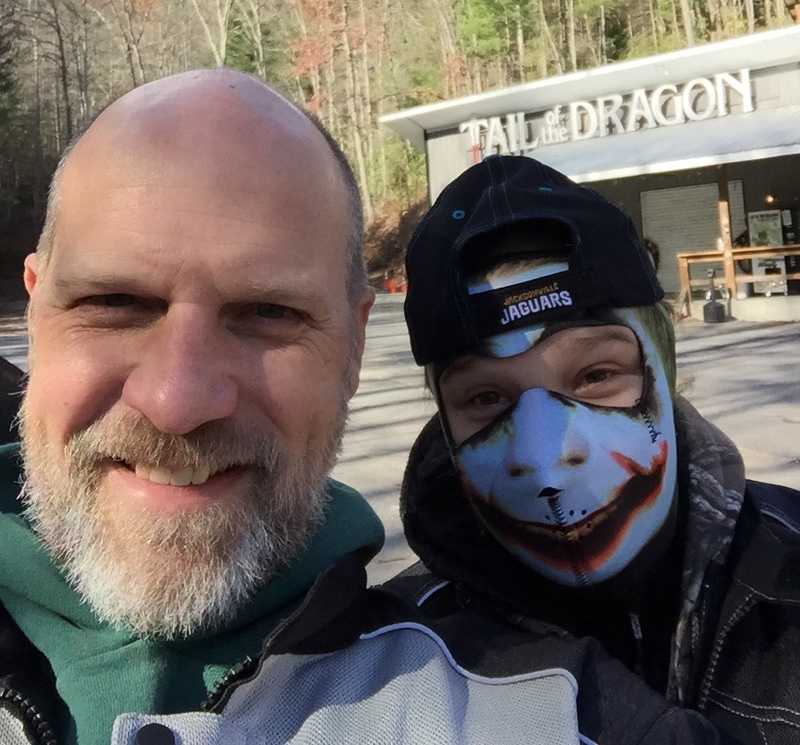

I didn’t always ride solo, though. All my children except the oldest, whose bulk paired with mine would have capsized us, joined me for the occasional ride. One son in particular yearned for the Hog life, so periodically he’d hitch onto the back and we’d go riding along rivers, under tree canopies, and through the tang of the Atlantic Ocean’s salt air. Our trips were short — an hour or two — but one day we learned about Tail of the Dragon, which claims to be “America’s number one motorcycle and sports car road.” Tucked into the Smoky Mountains between North Carolina and Tennessee, it boasts 318 curves in the span of 11 miles. Do the math. That’s a curve every 180 feet. If the road ran through the National Mall in Washington, D.C., and you started west from the steps of the Capitol Building, by the time you got to the Lincoln Memorial you’ll have turned 50 times. You’re changing directions more often than D.C.’s politicians. Tail of the Dragon draws so many riders that it has a website and a tourist shop and T-shirts and stickers. A giant metal dragon guards one end of the road. You can even take your picture by the Tree of Shame: a tree stuffed with wrecked motorcycles from riders who snaked the turns too fast. Excited, we planned our trek for Thanksgiving week. We stuffed extra clothes into the saddle bags, bought a set of helmet Bluetooth devices so we could communicate with each other and listen to music while we rode, donned our gear, and hit the road. Now, understand we live in Florida, so we don’t understand “cold.” I mean, we wore jackets and gloves and woolen beanies beneath our helmets, but by the time we got to Tifton, Georgia, I was shivering and my son had iced over. We pulled into Tifton’s Harley-Davidson shop where my son talked me into buying him some leather chaps for his frozen legs and a face mask that looked like Heath Ledger’s Joker. Then we saddled back up, I pulled on an extra hoodie beneath my jacket, and we continued north. The hoodie, chaps, and face mask helped enough for us to continue our trip, but only just. When we finally arrived at the tourist shop at the south end of the Tail, we discovered it was closed for the season. We’d never considered that a possibility, that an attraction would close in response to the calendar. It made sense, though. Only fools would ride this far in this weather, just to swing back and forth. Undaunted, we resolved to order t-shirts online, since we couldn’t buy any from the shop, took some pictures by the metal dragon and the Tree of Shame, and then we rode the Tail.

We didn’t need the foreboding influence of the Tree of Shame to ride with caution. Two passengers, freezing weather, a protective father, and a mutual cautious nature ensured that we rode “like a little bitch.” Regardless, we reveled as we rode, weaving and swerving through the curves. We didn’t care that our zigs and zags lacked zip — we were riding The Dragon! We wove the 11 miles, alert and exhilarated, then flipped around and wove them again. The sun emerged, warming our fingers, toes, and souls. Along the way, we pulled over on one climb overlooking a vast valley to enjoy the scenery. The mountain vistas stole our breaths. We don’t see mountains in Florida, so we soaked in the views. A few riders screamed past us on bullet bikes, leaning into the curves to grab the road. One rider stopped to chat — a black man in his late 50s, out with his friends, too old to be doing this but too young to give it up. He told stories about his riding club, and how often they ride the Tail, and we soaked that in, too. We felt the bond, the togetherness of riding motorcycles and being in the wind and living free. We took a few more pictures, my son posing solo on the bike as if he ran the show, and then we went back to our motel for the night.

We headed home the next day. The temperature dropped and the wind picked up, knifing through my mesh jacket and hoodies. I felt naked. Exposed. I shivered as I drove, my torso shimmying in some strange dance to generate warmth. This wasn’t a “Wow, this is chilly” kind of cold. This felt like hugging a glacier naked. At some point, we stopped at a Walmart and bought more hoodies and hand warmers to slip inside our gloves. And still we shivered. I started losing feeling in my fingers, so we stopped and bought mittens and more hand warmers that I could push down onto my fingers. We couldn’t give up; we had to get home. So we’d ride for awhile, then stop at a restaurant when we felt tough enough to keep going after a break, or at a motel when we didn’t. Our days started late and ended early, sprinkled with stops for warm food and hot coffee. It took us three days to get back, but we finally pulled into our driveway, our trip odometer hitting 1,111 miles as we parked. We vowed to return someday to Tail of the Dragon, but only in season.

Shortly thereafter, during post-Christmas sales, my son and I visited our local Harley-Davidson shop. The jacket I’d been lusting for — the thick, black leather jacket, festooned with the same skulls that decorated my motorcycle — was on sale. Super sale. Amazing sale. 20% off. Practically free, at only $420! I waffled, knowing how much warmer I’d have been on our Thanksgiving ride but balking at trading an orthodontist payment for a third motorcycle jacket. My son pushed, though, and I bought the jacket before I even figured out how to confess to my wife how much I’d spent on it. I shrugged it on like chain mail. My Hog uniform was now complete. I loved wearing that jacket. True, I still shucked it during the summer months, but in cool weather it made me feel impregnable.

During a morning commute in the summer of 2016, a guy with a white Silverado and a cellphone plowed into the back of my Camaro. I emerged unscathed physically; my rear bumper and psyche weren’t as lucky. $4,200 fixed the bumper, but I became somewhat skittish about both driving and, especially, riding. I also became more selective about when and where I’d ride. My motorcycle commutes became less frequent, and I also avoided the highway during rush hour when I did ride, opting for longer routes through back roads. I suppose I’d started to recognize the dangers of Hog life. Still, I never considered getting out. I continued to ride, feeling nearly as free as before, though always with a warier eye.

Fast forward to the fall of 2018. By then, my morning commute included dropping one daughter off at her bus stop and taking another daughter to her school. I couldn’t take them both with me on my motorcycle, and honestly I wouldn’t take even one in morning traffic. My bike sat in the garage during the week, and during quite a few weekends as well. My youngest — a freshman in high school — started pestering me about planning a day to pick her up from school on my motorcycle. She wanted to look cool in front of her friends. I started looking for opportunities to plunk her dreams onto my calendar, and finally I had a day that I didn’t have to take my older daughter to school: the Friday before Thanksgiving. That morning, my youngest and I drove the car to her bus stop. I dropped her off with her backpack and a helmet, so she’d have the helmet when I picked her up on my motorcycle that afternoon. I returned home, swapped my car for my motorcycle, and rode to work. This was my last day of work before a week-long vacation in Washington, D.C., to spend Thanksgiving with family. Traffic was light with the impending holiday. Perfect for a ride. The chill of fall let me wear my leather Harley jacket, so my daughter would definitely look cool when I picked her up.

My work encourages participation in a student mentoring program, and I’d visit my student most Friday mornings. Around 10:00 that morning, I left work, stopped to stuff Subway footlongs into my saddle bags, and drove downtown to Andrew Jackson High School where my student was a senior. Our mentoring relationship started when he was in 7th grade, when he was already 6’ 2” and aspiring to lead the NBA in scoring and blocked shots. Over the years, he added a couple inches, moved on from basketball, and we’d developed a strong friendship that bridged the age gap. During our visits, we’d eat lunch, discuss what he was learning in school, catch up on family and life, talk sports, and plan for his future. I’d break out my laptop and we’d learn a little about programming video games. We’d always have fun, though the school bells ensured the visits were always too short, and I’d always leave feeling happy and energized. During the visit on this particular day, we bragged about all the food we planned to eat for Thanksgiving and all the football games we were going to watch. True, the Jacksonville Jaguars’ season, which had begun with great promise, had already turned disappointing, but we still had hope that they’d overcome injuries and save their season. When the lunch bell rang, we wished each other a happy Thanksgiving and I geared up and rode away.

Let’s stop a moment and determine my approximate riding skill level. I’d ridden motorcycles about 9,000 miles total — a shade over 3,000 on my Honda and a shade under 6,000 on my Harley. To give you an idea of how far 9,000 miles is, suppose you fly to the home of Harley-Davidson: Milwaukee, Wisconsin. You haggle your way onto a shiny red Road Glide, complete with hard bags, stereo speakers, and Bluetooth for your phone. In the hard bags you stow a couple pairs of undies, three Route 66 t-shirts, and a toothbrush, hop aboard, and drive through the night. You motor through Chicago, past the University of Notre Dame, between LeBron James’ birthplace and the one title he brought to the Cavaliers, across Pennsylvania and New York and into Midtown Manhattan. You park, buy a ticket for the express elevator in the Empire State Building, and ride to the observation deck where Tom Hanks finally connects with Meg Ryan in Sleepless in Seattle. You descend, remount your Road Glide, and head back across the corn fields of the Midwest. You dodge tornadoes through the Great Plains and wind your way through the Rocky Mountains. You bake as you weave through the cacti, rattlesnakes, and steer skulls of the Southwest until you arrive at the glamor of the Hollywood Walk of Fame, gawking at Tom Hanks’ star and searching in vain for Meg Ryan’s. When you’ve had enough traffic and smog from The City of Angels, you cruise up the Pacific Coast Highway, skirting Silicon Valley and waving to the sea lions (which you mistake for seals) on Pier 39 of San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf. Hailing hippies and hipsters through Oregon, you drive into Washington state until you spy the Space Needle in Seattle where Tom Hanks lay sleepless. After a few lattes, you rev your bike and head back across the US, crisscrossing your earlier path through the mountains and flatlands and stretches of emptiness and wheat fields and soybean fields and corn as far as the eye can see, eventually venturing into the Deep South where they make moonshine, pick cotton, and play college football better than anywhere else. The backwoods finally yield to retirement homes, and you embrace the rays of the Sunshine State. Tracking the eastern coast of Florida and reminiscing about LeBron’s Heat titles, you finally pull to a stop on the beautiful beaches of Key West. You sprawl in the sand and sip Rum Runners out of plastic cups, but you’re not done with the 9,000 miles yet. Frankly, you’re weary and saddle sore and you hear your ass whine every time you pull on your riding gloves. Maybe you should have listened when they tried to upsell you to one of their CVO models with a seat like a sofa. You decide to head back to Milwaukee to save your whining ass. About the time you cross out of Florida and into Georgia, and depending on where along your travels you zigged or zagged — congratulations. You’ve driven 9,000 miles. That’s a lot of driving. You’ve seen the USA on two wheels and blown through “novice” and “intermediate” and landed on “motorcycle veteran.” You’ve muscled off the baby fat of inexperience and honed your craft and emerged a road warrior. Let’s temper that enthusiasm a bit, though — if you’ve averaged a reasonable 40 miles per hour during the drive, you’re only about 225 hours into Malcolm Gladwell’s fabled 10,000 hours of deliberate practice required for expertise. In that perspective, despite your miles of practice, you’re still a rookie. So that’s where I was: a road veteran but barely over 2% of the way to becoming a road expert.

Back to me and my 225 hours of practice, heading back to work from Andrew Jackson High. After heading south on I-95, I turned east on Butler Boulevard, known locally as “Jay-Tee-Bee“ after James Turner Butler, a Florida state senator no one’s ever heard of apart from his namesake highway. As I neared Gate Parkway — my exit — I changed from the middle to the right lane, still pacing with traffic at 65 MPH. Suddenly, I noticed a line of brake lights clogging the exit, backing up into the highway. My body, not brain, processed the cars, and reacted primally. My right hand crunched the front brake handle shut. I’ll never really know what happened next, though I’ve replayed those events in my mind many times. Perhaps gravel or oil caused my bike to slip, but I don’t remember seeing any debris on the road. No rain fell that day; the roads were dry. No cars were particularly close to me, so I don’t imagine that any vehicle struck me. I saw no rabbits or armadillos to throw off my balance. Perhaps my front tire, angled to the right to complete the lane change, locked up when I braked, lost traction, and spilled the bike sideways. I don’t remember going sideways at all, though, or coming at all close to having my right leg pinned between my bike and the road. I’ve reviewed those events in my mind many times, and the embarrassing conclusion I always reach is that I’d braked so hard that my bike stopped abruptly and I didn’t. I think I just flew over the handlebars. Regardless, the next thing I remember after the mob of brake lights was hearing a squeal from my tires and the slap of plastic on concrete. I hit the freeway face first. I remember seeing pavement scrape across my face shield, and then I remember rolling, around and around, down the highway. Lights, screech, slap, roll. Lights, screech, slap, roll. It all happened so fast, as if the event were singular, not plural, with no commas or even spaces between the words. LightsScreechSlapRoll. Almost simultaneous. And my motorcycle had simply disappeared. It was gone. I just rolled, like wet clothes in a washing machine’s spin cycle, like when you were a kid rolling down a grassy hill, elbows tucked fiercely, too fast to stop. I was a couple rolls past hitting the pavement before my brain processed: “I’ve had a motorcycle accident!”

I’d guess I rolled ten times, though it might have been half or double that. As I rolled, my brain eventually screamed at me to get off the highway before someone ran me over. I couldn’t respond immediately — I was spinning far too fast for voluntary motion. No matter how desperately I wanted to escape the road, though, I feared that blindly running to the shoulder might plunge me into the path of a car. I vowed to avoid the irony of surviving a wreck but dying while running to safety. While I whirled, I resolved to trade precious running moments to scan for a safe route. My momentum finally slowed sufficiently, and I leapt to my feet and turned to face traffic in a single motion. There I froze — half-crouched, muscles-tensed, like a squirrel — scanning oncoming traffic. Everyone had stopped, bless their souls. Everyone. All traffic had stopped. A wall of motionless cars gaped at me. I gathered this view as a snapshot, a quick mental shutter click. My momentum had rolled me one lane to the left of the exit lane, and I swiveled my hips like Barry Sanders, aimed for the shoulder, and bolted. No one has ever described me as “fast” or “quick,” but in that heat I was blazing. If any Jaguars coach had been standing on the shoulder with a stopwatch and a clipboard, he’d have offered me a tryout. Knees churning like pistons, feet smacking the asphalt, fists swinging with fury, I barreled off the road and onto the shoulder. I’ve never run faster.

As I reached the grass on the side of the road, people spilled from their cars to make sure I was OK. They quickly surrounded me, wide-eyed and concerned. An off-duty paramedic, serendipitously present, took charge and began peppering me with questions. Do you know what day it is? Do you know where you are? Do you know your name? I gave all the right answers, since my wits remained intact, but I couldn’t stop interjecting, “Oh, shit!” Over and over I spat the obscenity. “It’s Friday! Oh, shit!” “Yeah, I’m on JTB. Oh, shit!” “Rob. Oh, shit! Rob Warner. Oh, shit! Yeah, I know everything. I’m fine. Oh, shit!” Every third time I swore, I’d cover my mouth in embarrassment, but the words kept knocking my penitent hand aside. “Oh, shit!” And I kept trying to explain, while at the same time pleading for an explanation, “My bike was just gone! It was just gone! I was riding it and it was just gone!” I’m not sure what I expected; did I think someone would confess, “Sorry, mate. I’m David Copperfield, and I was just looking for a laugh. Just of flick of the wand, y’know, and poof! No more motorcycle. And I don’t reveal my secrets.” No confession came, despite my pleas.

My swearing finally slowed, and I noticed my left shoe and sock had vanished. The general area of my toes both stung like nettles and felt numb. I started to look down, and then abruptly yanked my head back up. I couldn’t look. My foot felt like the pavement had ground some toes off, and I couldn’t look. I said to the paramedic, “Do I have all my toes?” She looked at me strangely and said, “What?” I repeated, “Do I have all my toes? I can’t look.” She said that yes, I had all my toes, and I breathed easier. I looked, and indeed all five toes stared back at me, bloodied but present.

The paramedic told me to sit, and I complied, though I felt fine. Sitting felt silly. Sitting was for the injured, which I wasn’t. I’d lost a shoe, not a limb. Sirens wailed as police cars and an ambulance arrived. I felt sheepish at the attention. I knew I’d have some logistics to work out, but I felt healthy and well and ready to resume my day. I assumed I’d deal with the police, get my bike towed, and go back to work. I didn’t have a ready solution for my naked foot, but my work sits close to a shopping Mecca. I’d buy new shoes once I’d secured transportation. Most of my new Apple Watch had fallen victim to the road as well — the band still wrapped my wrist, but only a few wires indicated where the body of the watch used to sit. Still, these issues were minor, and once dealt with would free me to finish my workday and go home to pack for the family D.C. road trip.

If David Copperfield had indeed caused my bike to vanish, it had since reappeared. It lolled on its right side on the shoulder. I had no idea what path it traveled before it rested there — whether it had flipped or wobbled or been wheeled to its spot. I began to worry, though, that coworkers going to or returning from lunch would see it and assume something bad had happened. “Maybe I should call my wife?” I asked, and the Samaritan paramedic agreed that that would be a good idea. Pulling my still-intact phone from my inner jacket pocket — I told you that jacket wore like armor — I tapped my wife’s name on my phone. She picked up, and I blurted, “I’m completely fine!” I didn’t want to lead with the accident, as I didn’t want her to worry and think that I wasn’t fine. So I said, “I’m completely fine! Not a big deal, but I’ve been in an accident, but I’m fine. No need to worry. I’m completely fine.” I protested too much, though, and overplayed my hand. She later said that I must have told her twenty times that I was completely fine. Adrenaline and shock drove me to it. I mentioned that I was supposed to pick up our daughter from school, and maybe I wouldn’t be able to get there in time. So I would let her know on that. I acknowledged that they were taking me to the hospital for precautionary reasons, but that I was fine. I wore the hell out of the word “fine” in that phone call. We hung up and the paramedics wrapped my neck in a brace, strapped me to a board, and lifted me onto a stretcher, despite my protests that I could walk. They told me that policy was to head to the nearest trauma center, and off we went. The pain started to flare on the ride — an ache where my back touched the board — but I blamed it on the hard plastic board and its straps that kept me from adjusting position. I’d be fine once unstrapped and moving, I figured, so I ignored the toothache along my spine. I knew my whole body worked: I ran, I stood, I walked, I sat, I unbuckled and removed my Shoei helmet, I had all my toes. I was lucky.

A paramedic accompanied me in the back of the ambulance, checking my vitals and chatting as we wailed to the hospital. More than once, he warned me that if emergency room staff needed me to shed my apparel, they wouldn’t bother to undress me. They’d just slice my clothes off with scissors. If I liked my clothes, he said, I should take steps to preserve them. After silently considering and rejecting a striptease on the stretcher, I asked what I, a reasonable human being, should do. Was he suggesting that I yank my clothes off in the ambulance? What are the logistics of sliding into the emergency room on a stretcher in the altogether? He hastily assured me that no, I should keep my clothes on while we rode, and no, he didn’t know what I could do to save my stitches, but repeated that if I didn’t want my clothes shredded, I should do something. I don’t remember what t-shirt I wore that day, but reason dictates it’s one I at least liked. I pined more about the jeans than the t-shirt. In a world that stocks shelves with pants with even-numbered lengths, my inseam sits stubbornly at 31 inches. Finding jeans that fit both my body and budget requires more effort than I care to throw away, especially just to accommodate a hasty disrobing. While we rode, then, I fretted about my denim, even as the ache in my back grew louder. I kept feeling like I had to flex my right side to keep from rolling left off my plastic plank, and I wondered why the plank wasn’t level.

We arrived at the emergency room where people started poking me and telling me to wiggle various fingers and toes. “Does this hurt?” they would ask as the pressed on my stomach or chest. I’d answer no, that none of what they were doing hurt. The only thing that hurt was my back where it was strapped to that plastic board, so really I just hoped they’d hurry because I figured the board, not any injury, authored that pain. I’m guessing this first wave of examiners were interns, because someone walked up in a white coat and a stethoscope and they said, “It looks like he’s fine. He says he’s fine. Nothing seems to hurt him. Do we just let him go?” The doctor cloaked in the white coat and the wisdom of experience said, “Absolutely not. We’ve had a motorcycle accident, so we’re doing a full workup.” They rolled me into a room and ordered X-rays and a CAT scan. They offered me pain medication. I thought of America’s opioid crisis and Breaking Bad and Bubbles in The Wire and I said no. Well, I half-jokingly asked if they could give me “edibles,” since marijuana is medically legal in Florida now and doesn’t turn you into a meth head. They said that no, they don’t dispense any marijuana products, so I dealt with the ache au naturel. While I lay there, bored and thinking I was soon headed back to work, my wife Sherry walked in with my Tail of the Dragon companion, Russ, and the daughter cheated out of looking cool, Leila. I don’t know if I was more surprised that they’d found me, or that they were there at all — hadn’t I told Sherry I was fine? She asked me what they’d given me for pain. I tried to explain about the opioid epidemic, and she spun on her heel and chased down a doctor to give me pain medication. Meekly, I complied. Another lucky stroke.

My oldest son, Tyson, had been headed out to lunch when Sherry called him with my news. He drove to the accident site and rescued my laptop from my fallen motorcycle. He also called a towing company and had my motorcycle hauled to a repair shop. He then joined us in the emergency room. My daughter Camie called out of work and Russ drove home, picked her up, and brought her to the hospital. My middle son, Jacob, was in Atlanta, playing in an 8-ball tournament, so couldn’t come. He kept texting, trying to figure out what was going on. A police officer came in and took my statement about what had happened. Still bewildered, I recounted the events as best as I could remember and interpret (I didn’t mention David Copperfield). He said my story matched those of three on-scene witnesses, and that he wasn’t going to issue any citations. I hadn’t even considered that I could get a ticket heaped atop this mess.

There I lay, strapped to that infernal plastic board. Only it and the neck brace caused my back pain, I’d decided. And now the back of my head began to hurt where it touched the unyielding plastic. I wanted off the board to end the pain, but they weren’t yet confident they could move me. I asked Sherry to hold my head off the board, and she slid her hand between my head and the board, cupping it and providing a sort of pillow that gave me some relief. She later confessed that my head pain terrified her, worrying her about what it might portend. Emergency rooms elongate time, and the wait stretched uncomfortably. Finally, they decided to admit me for observation and X-rays, and needed to swap my t-shirt and jeans for a hospital gown. As the paramedic had warned, they didn’t want to jostle me to remove my clothes, and asked permission to hack them off. In a stunning betrayal, my wife crowed, “Cut ‘em off!” I protested, mouth agape, but she shushed me as a horde of hands held me down and snipped off my t-shirt, jeans, boxers, and remaining sock. And then threw a gown on me. The clothes went in the trash. I still haven’t replaced the jeans. Too much work.

When they took me for X-rays, I noticed that contorting myself on their commands hurt more than it usually hurt for an old guy like me to turn those ways. Still, I struck the poses they told me to strike and held the positions they told me to hold, and they took all the pictures they wanted. The CAT scan, as I recall, required lying still — a skill I’d mastered by at least my 20s. After both rounds of tests, I returned to the emergency room. A doctor walked in soon after and said, “You’re a tough son of a bitch.” I suppose that should have made me worry, as bad news was clearly coming, but I let my vanity fill the moment. Of course I’m tough. I ride a Harley, dammit! Then he dropped the X-ray results: five broken ribs. They later showed me the X-ray. You know how the doctor will walk you through an X-ray, pointing out things your untrained eye doesn’t detect? Radiologists go to school to learn how to read X-rays, and can see the hairline fractures that you can’t. Well, these weren’t hairline fractures. I needed no training to see all five breaks. I could see the ribs, flat and wide, snapped in two. The breaks had happened around my back, near where the ribs attach to the spine. It looked like someone had stomped their heel through a wooden shipping palette. This explained the pain that had been creeping up on me. I gave up going back to work that afternoon, and also leaving for our trip the next morning. I looked at my wife and said, “Maybe we can leave Tuesday.”

That doctor left, and another doctor arrived with the CAT scan results. She said, pointing to my wife and son, “Do you want them here to hear this?” My stomach lurched and my brain froze. In that moment, I knew I was going to die. I had gone from feeling unscathed and lucky, to dealing with some broken ribs, to suddenly facing death. And the doctor wanted to know whether to dump this grim news on my wife and son. My brain screamed to shield them. If I were dying, they couldn’t know. That was too cruel. That makes no sense, I know, because if I were dying, they would know soon enough. Still, my impending death seemed like a story they’d need to creep up on, later, experiencing in small bites that I’d figure out how to spoon them, rather than swallow all at once. I whispered, “Is it bad?” She gave me a funny look, so I repeated, a little louder, “Is it bad?” She said, “Um, this is just HIPAA privacy rules. Do you want them to hear your private medical information?” The tension dissipated. I resumed breathing. I wasn’t dying. She was just following privacy laws. I nodded and said that they could stay. She then explained that, in addition to the ribs, the accident had lacerated my spleen and punctured a lung. Both were concerning, but neither was lethal with proper care. Not time for streamers and balloons, but at least I wasn’t about to die.

She proceeded to lay out the next steps: they’d watch me, measuring certain blood levels at intervals, and if the numbers didn’t indicate that my spleen was stitching itself back together, they’d whisk me into an operating room and yank it out. Some of the gravity returned to the room. Excising an organ, one that I’d carried with me and nurtured my entire life, sounded serious. Her tone sounded more bantering than solemn, though. She came across as someone who excelled in school, caused people to feel embarrassed for her at parties when she said the wrong thing at the wrong volume, and spent her days off from work at Renaissance fairs in costumes she’d made herself. I felt safe. So I bantered back, “I know what you want to do! I’ve seen Grey’s Anatomy! You just want to operate!” She laughed and conspicuously didn’t deny my accusation. She explained, though, that people live fine without a spleen. Somewhat mollified, I still felt like keeping my full set of organs. After all, why would evolution encourage me to grow an organ I didn’t need? Didn’t it learn its lesson from the appendix? I later googled spleens and their absence, and learned that yes, you can live sans spleen, but you spend the rest of your life catching colds and popping antibiotic pills. I willed my spleen to heal.

Somewhere between bouncing my face off the pavement and swearing on the side of the road, I decided I’d ridden my last motorcycle. Once I could no longer tell myself or others that accidents were for other people, not me, I knew I couldn’t ride again. I come from a long heritage of guilt and a general discomfort at attention. My sheepishness began on the side of the road as people full of concern gathered around me. I knew, from the first time I hopped on a motorcycle, that I’d assumed more risk. By crashing my bike, I’d dumped the consequences of my risk on others. Shame had set in by the time I got to the emergency room, and grew a little with each new visitor. I apologized to the nurses. I apologized to the doctors. I apologized to my wife. Several times. I apologized to my father and my children. My wife kept shushing me, thinking it ridiculous that I apologized. I was the one hurt. Of course people should take care of me and worry about me, she explained. I couldn’t shake the guilt, though, of creating the situation. I knew the risks, and I bought a motorcycle anyway. When my father-in-law walked into the emergency room, face etched with worry, I blurted, “I know you told me so. And I’m selling it.” He gave me a thin smile, the corners of his mouth lifting just into his mustache, and said, “I wasn’t going to say anything.” I replied, “I know. That’s why I said it first.” We were both lying, and we both knew it.

My father, usually quick with a grin and a Reader’s Digest joke, sat in the room, solemn and quiet. My mother was in Dallas for the week, visiting my sister and her twin babies. I begged my father not to tell my mother anything, fearing she’d abort her vacation. He’d already communicated to her a vague blush of what had happened, so I begged him to get her to stay in Dallas. I texted my sister to assure her I was fine and recovering, so Mom had no reason to come see me. I couldn’t bear to ruin another vacation. Thankfully, she stayed.

They took me to the Intensive Care Unit so they could track my oxygen levels and monitor my punctured lung and platelet counts. My platelets, apparently, would tattle on whether the crack in my spleen was healing or not. I spent two days in the ICU among the dying. My wife would give me periodic reports of tearful crowds in the hallways who had lost loved ones. The sounds of suffering and sorrow filtered through my door at times, a reminder of how differently my story could be unfolding. Most motorcycle stories involve death, dismemberment, or paralysis in some form. Mine had been a scare and an inconvenience. Though any adrenaline rush had long since evaporated, a cocktail of drugs kept me comfortable. I wasn’t dying. My platelet counts trended the proper direction, perhaps in response to my wife’s anxiety about the possible surgery, and thwarted any scalpel’s run on my spleen. My blood-oxygen levels yo-yoed like Twitter stock, so they threaded a breathing tube beneath my nose, making me look like the warning figure on a “No Smoking” campaign poster. I had worried a lot of people, but I was going to be OK. We played the “what could have been” game a little, perhaps to ensure we were sufficiently grateful for good fortune, but when I said out loud, “What if I’d already picked Leila up from school?” my wife cut me off. Just the beginning of the thought of our baby flying through the air and tumbling on the highway sickened us beyond our capacity to imagine, and we fled from the thought. I can’t even think it now.

I slept off and on, always on my back, and always with my head elevated. Any other position brought excruciating pain, my ribs clacking together as they clambered for position. Historically a side sleeper, I had to learn to sleep on my back for the next two months. Even stomach-sleeping proved impossible, the broken ribs hanging down and leaning on my organs. The hospital bed, as most do, had controls to incline its head like the beds on late-night TV commercials. Flat didn’t work for my pain, and I’d cycle through various angles throughout the day and night. To reach the bed’s controls required twisting my body, however, which was still too painful, so I had to ask others to raise and lower my bed for me. I felt as helpless as a newborn. I would later use a wedge pillow at home to achieve the necessary elevation. Both my left ankle and right shin bore traces of road rash, and though my leather gloves had protected the skin on my hands from the ravages of the road, the hands themselves had swollen from the trauma. Ice on my hands reduced the swelling, and ointment on my scrapes kept infection at bay. Since I was stuck in bed, I thought I could use the time productively. I tried to read a novel or write code on my laptop — I always have technologies I want to explore and side projects I want to move forward — but I couldn’t get comfortable and I couldn’t focus. I downloaded a word game onto my phone, and spent far too many hours mindlessly finding anagrams. Some days, I didn’t even bother putting in my contacts, without which I can barely make out the “E” on the eye chart. I rested, slept, and gradually healed.

When you enter the hospital as a patient, you surrender dignity and privacy. My wife, who’s birthed five babies, understands that better than most. In the emergency room, when they snipped off my jeans, t-shirt, and boxers, I donned a resigned smile. How can you complain about a little nudity to a woman who five times has lain for hours in a roomful of strangers with her legs splayed? Later, a nurse gave me a sponge bath, and went to great pains to maneuver a towel as a masseuse would to keep my naughty bits concealed. I scoffed inwardly. I had no privacy. I had no dignity. I swapped those for a hope to live. My family became the victims of my exhibitionism, however. For the first few days in the hospital, I couldn’t get out of bed to go to the bathroom. Instead, they gave me a bottle with a handle that hung from the side of my bed. My arms were yet hopeless, however, so not only couldn’t I hold the bottle, I also couldn’t hold my penis to direct my urine stream. I’d announce whenever I had to pee, and someone — usually my wife — would grab the bottle, raise my gown, lift the blanket, position the bottle, and gently guide my penis into it. I’d pee, she’d dab me with a tissue, and then dump the bottle. Sometimes, though, my eldest son was the caretaker-on-duty in the room. He’d perform similar duties, though he’d always strap on latex gloves first. Everyone felt a little better when my arms worked sufficiently to hold my own penis, and then better still when I could also hold the bottle. Silent cheers (mixed with trepidation over whether I’d fall) celebrated the moment I could finally wince my way out of bed and wobble to the bathroom to pee on my own.

Unassisted urination arrived in less than a week. Defecation presented its own challenges, however. Before I’d been wheeled to the ICU, I realized not only my immobility, but my inability to sit or stand. When you can’t walk, sit, or stand back up, you can’t use a traditional toilet. I’m sure they have some solution for that scenario, but I didn’t want to find out what that was. I refused to eat. I didn’t know how long I could hold in my current inventory, but I knew not to add to the load. Peeing in a bottle while prostrate is a trifle compared to the logistics of pooping in bed. Three times a day, they brought me a tray of hospital grub. Three times a day, I sent it back untouched. Yes, I drank the juice, and drank plenty of water besides, but until I could manage walking to, sitting on, and standing back up from the toilet, I was Gandhi on a hunger strike. Doctors would tsk at me to eat my food, but I held firm, aided by the oxycontin that not only quelled my appetite but also stopped me up. By the time I left the hospital, I’d lost ten pounds. When I could finally walk and negotiate a toilet, though, I began nibbling at my meals. My family and I then discovered a new way to get close. We discovered how hard wrapping your arms to your posterior can be with broken ribs. I simply couldn’t reach my backside. They had to wipe me. Any dignity I’d held on to evaporated. Wiping duty generally fell on my wife, but my oldest son’s timing saved him. His shifts never coincided with my shifting bowels. My second and third sons weren’t so lucky, though, and were the only ones present during a critical moment. “Jacob, prepare yourself,” I said. Fear splashed across his face, and he said, “Um, I can’t do it. I’ll throw up.” I pressed; he whined like a caged beagle. “Nooooo, I’ll seriously throw uuuuuuup.” Imagine Tom Haverford from Parks and Recreation. My third son Russ had to step into the breach and wipe my bum. Now I know at least he can take care of me in my old age. I’ve bumped him up in my will.

That first Sunday after the accident, hospital staff came to get me out of bed. A few strong men brought a walker and said it was time to get some exercise. They lowered the guard rail on the right side of my bed, supported my arms, and started helping me up. I turned to my right and screamed. Pain coursed through me like lightning. I’d rotated my torso a couple inches and felt as if someone had shanked me in the back. I flopped back into the pillow and whimpered. These men were professionals, though, and leapt into action. They pulled the footboard off the end of the bed, explaining that I could come straight off the end instead of twisting to the side. While they worked the controls to raise my head and lower my feet, I steeled myself to try again to stand. Again, strong hands grabbed my arms. Again, I barely moved, cried out, and froze. Pain owned me. It rendered me helpless. I cowered, refusing to move or blink or do anything that might invite the pain back. I told myself I’d never move again — just don’t let the pain return. Nothing mattered beyond lying completely still. I relinquished my “tough son of a bitch” persona without a fight. “I can’t,” I said. “I can’t do it.” Startled at the amount of pain I felt, these men let me off the hook. They got a nerve blocker added to my drug buffet and promised to return later. I rested and resolved to do better.

A few hours later, they returned. The nerve blocker had lifted the pain a little, and my determination had risen a little, too. They again removed the footboard from my bed, and raised me to a sitting position. I steeled myself against the pain and they helped me straight off the end of the bed into a standing position. They wedged the walker under my forearms as I willed myself to breathe. I slid one foot forward gingerly, my sock stuttering across the linoleum. Once my foot had traveled a few inches, I stopped and shifted weight to it. I was moving! I was walking! I hurt, but I was mobile! Suddenly, though, the muscles in my back clenched. Hard. White-knuckle grip. Mr. Universe flex. The slab of muscle on the left side of my spine — the trapezius — gripped my broken ribs and squeezed. Bone shards stabbed muscle. I yelped. My sister was there to visit, and with startled eyes she hovered in her best “how can I help?” pose. I willed the muscle to relax. It ignored me. I begged it to relent. It squeezed tighter. Sweat erupted on my brow. The muscle didn’t sympathize. The men urged me forward. I hazarded another shuffle, and still the muscle clutched desperately. I mustered a third step, sweat and pain dripping from my face, before they decided I’d had enough exercise and helped me scuffle back to bed. My sister stared, aghast, seeing the pain and not being able to fix it. Still, I had walked! I was ambulatory!

The next day, an occupational therapist showed up without her heart. Her job: get me up and moving. Pity lay outside her job description. She didn’t have time for whimpering. She didn’t celebrate baby steps. She got you up and made you walk. She dropped the guard rail on the side of my bed and said, “OK. Let’s go.” I stared for a moment, twisted a little to the side, and my ribs knifed me. I sat back. She told me again to twist off the side of the bed. I said no. “Yesterday,” I said, “they had me go straight off the end of the bed. I’ll do that.” I assumed she’d understand. She didn’t. She again told me to twist off the side. “What will you do when you get home?” she asked. “You’ll have to exit the side of your bed, and the footboard doesn’t come off that.” “But I’m not at home!” I protested. I again offered to go off the end of the bed, and she again said no. We glared at each other, our wills locked. I won. She rolled her eyes and removed the foot of my bed, and I went straight off the end. I would have grinned victoriously if I weren’t in so much pain.

Again, I slid a stockinged foot forward, and again, my trapezius flexed and impaled itself on jagged bones. I focused on that muscle, willing it to relax. This time, it listened. It relaxed its grip. I took another step. The muscle started to flex, and I thought of daffodils and wood nymphs. Well, not really — I just kept telling my muscle to play it cool, and it backed down. Another step, another minor jerk, and another surrender. By the fourth step, I had control. I walked out the door of my room and down the hallway, leaning across my walker, taking the floor one tile at a time. I walked the entire hallway loop — probably 200 feet — and returned to my room, exhausted but proud. I never saw that therapist again.

Medical personnel watch a parade of patients through their years of service, so I imagine practicality dictates a certain emotional distance. I figured that the best way to remind them that I was a person with hopes, dreams, fears, pains, and a life back home was to talk. Engage them. Ask them their stories. Be both human and a little bit memorable. It’s a bit like hitting on someone in a bar, I guess, without the flirtation. So I would talk to the people that attended to me, asking them their stories. I’ve since forgotten much of what I learned, but in those moments I was the therapist they never had, the best friend they didn’t know they needed. I’m a software developer. I chose a career that puts me alone at a desk with a soulless machine. I like people like I like aspirin: in small doses, and not too often. In the hospital, though, I was a hail fellow well met. In moments of introspection, I questioned the source behind my garrulousness, as it closely resembled how talkative I become after a few beers. Still, I greeted each person coming into my room like I wanted to earn their business that day.

One person I met stands out. In stockinged feet, I stand just over six feet tall. That “just over” part is a rounding error, depending on the time of day and life’s burdens. Two things you learn when you’re a man who could serve as a measuring tape for six feet are:

- SUV designers make liftgates whose “open” position is just above eye level, so you don’t see it, but still below “top of head” level, so you whack your head every time you unload groceries.

- The world is full of 5-feet-10-inch men who believe they’re six feet tall.

The men who fall into point #2 out themselves when they ask me, “How tall are you? Six two? Six three?” I say, “No, I’m six feet.” Then I brace myself for the inevitable reply: “No, you’re way taller than that, because I’m six feet.” I always feel a little sad for them, knowing I’ve wounded their manhood.

One of these 5-feet-10-inch men was a nurse who waited on me. He hailed from somewhere in the Caribbean with the melodious accent to match. He had me stand, and said, “Whoa! How tall are you? Six two? Six three?” I sighed and said, “No, I’m six feet.” He replied, “Wow. I thought I was six feet, but I guess I’m not!” I liked him already. He told me about his 6’ 7” son who played college basketball. If we snagged a copy of the game program, I suspect he’s listed at 6’ 5” and tops out at 6’ 3” in Air Jordans. Anyway, this nurse, like all the others, was delightful. They all took good care of me. Around the clock, they’d bring me pills, administer treatments, speak soothingly, and encourage me to heal.

Resting covered the treatment for my broken ribs, and time allowed my spleen to heal, but I still had the punctured lung to fix. The treatment for healing a punctured lung, I learned, includes something they called a “breathing treatment.” They would hand me a sort of miniature hookah, with a vaporizer, a reservoir for liquid medicine, a plastic tube, and a mouthpiece. I’d inhale deeply, using mouth not nose, and suck in medicinal vapors. Then I’d exhale. I’d do this until the medicine ran out, which took, if I recall correctly, around five minutes per dose. Sounds pleasant and calming, right? Hookah comes in an array of flavors, ranging from “Gummi Bear” to “Flower Power.” One list I later found by googling “best hookah flavors” includes a flavor scandalously called “Sex on the Beach” and another with the ambitious name “Ambrosia.” Food of the gods. Maybe pharmaceutical companies can’t hit such a lofty target with “breathing treatment,” but surely they can land somewhere in the neighborhood of the bubble gum-flavored Amoxicillin. It turns out, sadly, that “breathing treatment” comes in only one flavor: “Dog’s Ass.” Calling it “terrible” undersells how bad it tasted. Six times a day, for five minutes each time, I felt like I was gulping flatulence. It curdled my tongue. I soldiered through the first few treatments, then started dropping hints about how vile they were. One night, the duty nurse said he’d let me skip a 4:00 AM treatment so I could sleep. I cheered. Then I got greedy. I leaned on one young nurse heavily enough that he said he’d drop them entirely, if I wanted. Just as I started to take him up on his offer, though, I remembered that “breathing treatment” was purportedly treating something, and that something was my leaky lung. Chastened, I meekly said that no, I’d suck that Dog’s Ass and whatever else it took to heal. From then on, I kept my whining to myself, and faithfully finished my breathing treatments.

Breathing treatments medicated my punctured lung; a different contraption called an “incentive spirometer” exercised it. Designed to inspire patients to, well, inspire more deeply, a spirometer measures how deeply and slowly a patient inhales. Deep and slow inhalations fill and exercise the lungs, healing and strengthening them. A spirometer is made out of hard, clear plastic, with a vertical tube with gauge marks painted up the side. A piston sits inside the tube, resting at the bottom. A flexible tube with a mouthpiece on its free end attaches to the base of the vertical tube. Sucking on the mouthpiece causes the piston in the clear tube to rise in proportion to the strength of the suction. The trick is that, by setting goals for how high the piston should rise, you incentivize patients to do a lung work out. We call that “gamification,” and studies link making games of tasks and measuring milestones with increased motivation. I was given a specific mark for the piston to hit, and instructions to play this game several times a day. People would cheer whenever I hit the mark — not the confetti-and-piñata kind of cheering, but the “Way to go, Idaho!” kind. I played along, but every time I inhaled on that spirometer, I felt like a sucker. People would have to remind me to use the spirometer, since it really wasn’t a fun game. I’d get light-headed and the mark was hard to hit. I might hit the mark once out of twenty tries. Still, I inhaled and acted inspired, hoping my lung was responding to the conditioning.

The spirometer did provide some humor, however. After one session of breathing deeply and slowly, I set it down and, exhausted, fell asleep. Since I still struggled with the range of motion in my arms, I had dropped my arms straight down and set the spirometer in my lap. Sherry walked in to see the spirometer’s flexible tube snaking from just below my waist, and immediately snapped a picture. She and my father-in-law, who never grew out of seeing the goofiness in life, couldn’t stop giggling. We needed the comic relief.

By Tuesday, five days into my stay, the doctor on duty started making noise about discharging me and sending me home. My breathing still wasn’t under control and my blood oxygen levels bounced crazily. Normal human blood oxygen levels, I learned, range from 95% - 100%. Anything below 90% causes concern, and falling below 80% causes Klaxon horns to blare. While my oxygen levels crept into the low 90s at times, they mostly hovered in the mid 80s, and occasionally plunged into the 60s. When I’d dip, they’d stuff that oxygen tube under my nose and tell me to breathe deeper. They’d ask again if I were a smoker, and, with slitted eyes, would accuse “Are you sure?” when I’d tell them I wasn’t. I’d focus, breathe deeply, and lift my levels to the high 80s or even low 90s. Then they’d leave the room, my focus would slip, and I’d slide back to the mid 80s. Their timeline wanted me to be well, though. The on-duty nurse started to vocally doubt the accuracy of the machine anytime it read low. When the reading would shoot back up, she’d take it as confirmation that the machine had fixed itself, and that I was fine. She’d clearly been tasked by the doctor to prep me for discharge. She soon had to choose, however, whom she feared more: her boss or my wife. Because my wife isn’t yet ready for widowhood, she told that nurse to tell that doctor that I wasn’t well enough to go home yet, and if the doctor ever bothered to come see me, he’d see that for himself. Back and forth ran the struggle. The nurse would come explain what the doctor had told her, that I should be fine and it was time for me to go home. My wife would send her back out the door with her own message: I was not fine, and I was not going home. I never doubted who would win and who would lose. I stayed in the hospital six more days.

The next day, Wednesday, my Renaissance fair friend was back on duty, and grew concerned with the shallowness of my breathing. She laid a stethoscope on my chest and tapped around, and then ordered X-rays to check for fluid around my lungs. She may have tossed around the words “Hemothorax” and “pleural cavity,” but the ones that made me most uneasy were “chest tube.” I’m generally unmoved by the slew of Trypophobia-inducing images the Internet offers, but the thought of auguring a hole in a human and inserting a tube makes me shudder. I grew up with a mother who trained us for catastrophe. Once, when we were in elementary school, she taught us how to perform an emergency tracheotomy with a ballpoint pen in case a weightlifter ever dropped a barbell on his Adam’s apple. Yes, the lesson was that oddly specific — I assume she’d seen a story on the news. Anyway, I pretended to pay attention as she had us feel for the ridges and valleys in our tracheae to determine the proper point to stab a pen into, all the while knowing that if Bic and I stood between a strongman and salvation, he’d already taken his last breath. Still, if it took a tube to fix my breathing, I knew I’d have to endure. The doctor said we’d give it another day.

The next day was Thursday. Thanksgiving. Instead of feasting with family in D.C., I nibbled on pressed turkey while my wife sponged sweat from my forehead. The doctor decided to move forward with the chest tube, and explained that chest tubes came in three diameters. The diameter of the tube they’d need depended on the viscosity of the fluid in my pleural cavity, or the space between my lungs and the sac that surrounds them. The viscosity of the fluid depended on how much of it was blood. The smaller the chest tube, the smaller the hole, the quicker the procedure, and the sooner the recovery. Based on the X-ray results, the doctor said that I’d probably need only the small tube. They’d use a needle to make a small hole, and then insert the tube. She asked if I was OK with the presence of an intern — that’s when I learned that this hospital, like the one in Grey’s Anatomy, was a teaching hospital. I affirmed that I was OK with that, and the doctor told her student to proceed. I guess I hadn’t really understood the question — I thought the student was observing, not performing — but I mentally shrugged and steeled myself for the needle, whose pinch is never as bad as I prepare for. They had me roll on my right side, to which my ribs protested, but I gritted my teeth, gripped the side rail to hold myself in position, and lay still. After numbing the area on my left side, they pushed in a needle, put in the small tube, and willed my chest to drain. My chest refused. After some muttered imprecations and a whispered “c’mon, c’mon, c’mon,” they conceded that they’d have to graduate to a bigger hole and a bigger tube. The medium tube netted the same results as the small tube, so they brought out the big tube, a little over a half inch in diameter. I’d graduated from a little stick to a carving job. They sliced the skin, then started slicing layers. I lamented the gym progress I was losing as the muscle parted. To finish the job, I remember they really had to lean in, and then I heard and felt a pop when the geyser began. They hastily threw tape around the tube, holding it fast. The receptacle by the side of my bed began to fill, and they told me to get some rest. We were under another surgery watch, and my progress over the next 24-36 hours would decide whether I’d need surgery to repair the lung. They check the hole in my side a few hours later and found a slow leak, which they plugged with a swath of more adhesive tape. Over the next few days, over 1000cc of fluid, mostly blood, drained from my chest. In volume, that’s somewhere between the sizes of the engines of my two motorcycles. Removing that fluid relieved pressure from my lungs, but I still struggled to breathe at the levels considered healthy. I continued with breathing treatments and that damned spirometer.

And so the days went, fading in and out, a few memorable events punctuating a dim monotony of swallowing pills, breathing deep, and sleeping. They discovered, after scrutinizing an X-ray, that my left ankle bone had indeed been chipped, which explained its continued puffiness. They also had to treat the cellulitis that had beset it, the infection creeping in through the raw scrape tattooed on it. A crowd of friends passed through, asking for the story and bringing well-wishes. Some visits I slept through. Others, I didn’t remember, and had a few instances post-hospital when people mentioned visiting me in the hospital and were surprised that I didn’t know. “We watched the football game together!” they’d say, and sometimes that would be enough to jog my memory, and other times I still had no clue. For many visits, though, I was awake and appreciative for the company and kindness. Through it all, at least one person from my family sat in my room, ready to raise my bed or hold the bottle or call a nurse. I’d see them plan shifts, uncomplaining, making sure someone could be there day and night. When nurses would wake me in the night for a dose, I’d see someone curled on the couch. Often, that sleeping person was one of my two older sons, both of whom struggle to get enough sleep under ideal circumstances. My heart would swell as they’d hop up when the nurse would come in, asking if I needed the bottle or a drink or anything. More than once, I felt tears form as I contemplated their sacrifice. They all surrendered their vacation weeks and comfortable beds to attend to me. I felt both grateful and guilty.

As my second weekend in the hospital arrived, Sherry started pushing me to heal faster. Spending days and nights at the hospital during Thanksgiving week wasn’t my family’s favorite way to fill vacation time, but at least it wasn’t encroaching on scheduled activities. School and work started back up on Monday, though. They had to resume their lives. And I agreed. Besides, life back home hadn’t paused just because I lay in a hospital bed. We had nine people and three dogs under one roof at the time, so life never got quiet. During my hospital stay, Jacob’s dog had spent a day throwing up all over the house, including four dishrags she mistook for Scooby Snacks, and the next day in a $2,400 surgery to remove the rubber bristles from a basting brush that obstructed her bowels and caused the vomiting. Also during my stay, our oven had decided, after 19 years of faithful service, to call it quits on Thanksgiving day, making everyone scramble to ferry uncooked dishes to a nearby friend’s to cook and then return home in time for Thanksgiving dinner. Sherry had had to straddle hospital and home for over a week, and now she’d have to wedge work in as well. Most importantly, though, the fluid that had leaked from my chest tube and lurked below the adhesive tape had started to ripen. I could really smell myself, and it wasn’t pleasant. I needed the chest tube gone so I could shower off the stench. I pushed hard to leave Sunday, but the same doctor who tried to push me out the previous Tuesday wouldn’t let me leave. I guess those oxygen levels mattered after all. Over the next two days, nurses measured my oxygen levels and asked whether I was using my spirometer and accused me anew of smoking. On Monday, I pushed harder. I refused the oxygen tube, as that was a disqualifying crutch for discharge. I told that day’s head nurse that I must just be a 90% kind of guy, fudging the numbers upward a bit in what I hoped would anchor the discussion. He replied that really no one is a “90% guy,” and that everyone who’s not in immediate peril runs in the high 90s. I later learned from my father, though, that his oxygen levels always hover around 93%, so I feel exonerated. Genetics keep me oxygen-starved, and I’m surviving. I may yawn a lot, and present as if I’ve spent 20 years puffing two packs a day, but I’m breathing all the oxygen I need. So for a critical 15-minute window, while they watched, I inhaled like I was preparing to cave dive. I didn’t make it. I didn’t hit high 90s. But I wheedled enough that I convinced them that I’d be safe at home, or perhaps they were just tired of my whining. They warned me that my pain medication dosage would be cut in half once I left, which didn’t scare me because I could lie still virtually pain-free. A little more pain wouldn’t be an issue. They slipped out my chest tube, filled out my discharge papers, gave me that spirometer and told me to keep using it, put me in a wheelchair, and wheeled me out of the hospital.

On the evening of Monday, November 26th — ten days after the accident — I finally went home. That night, I texted my boss that I was home and what my work plans were. We had an all-night data center move scheduled for the coming Sunday, December 2nd, and then I had a three-day vacation planned for the following Monday through Wednesday. I felt sheepish about taking a vacation after missing so much work time, but Sherry was presenting at a conference in Orlando and we’d had this getaway planned. My text to my boss said I’d go in Sunday for the data center move, take my vacation, and return to work on Thursday. Without waiting for a reply, I set alarms for my pain meds and went to sleep.

Remember the warning that they were halving my doses when I left the hospital? Sometimes cutting something in half introduces a gentle reduction. In this case, it flung me off a cliff onto the sharp rocks below. Even though I faithfully awoke to my middle-of-the-night alarms and took my pills, by the time morning arrived I hurt everywhere. I hurt in places that had never hurt in the hospital. Sharp pains. Dull pains. Focused pains. Fuzzy pains. The hospital and its full doses had kept mountains of pain at bay. The half doses weren’t equal to the challenge. I felt as I imagine Rocky Balboa felt after fighting Ivan Drago in Rocky IV. What had I been thinking? No way was I going to be able to go to work Sunday. I picked up my phone, with difficulty, and saw my boss’s texted reply: “You have lost your mind. You are not coming back to work this year! I will have your badge turned off.” She knew, bless her. I texted back, confessing how badly I hurt, and how I had no idea this was coming. She said, “Yep! You were high as a kite.” Now I understood my chattiness in the hospital: I was doped and euphoric. I stayed in bed and took my meds faithfully. I didn’t go to work on Sunday or the following Thursday, and I didn’t go to Orlando with my wife. We agreed that me crying in a hotel room all day would be fun for no one, so I stayed home and she enjoyed the conference without me.

While in the hospital, I had filed for short-term disability, and thus embarked on an unfamiliar path in the confusing jungle of health insurance. I learned, at least in Florida, that short-term disability merged with workers’ compensation. As in, they married, formed a union, and stand as one. By filing for short-term disability, I now fell under the umbrella of workers’ compensation, even though my injuries weren’t work related. I’m not sure how a software developer could even sustain a work-related injury, unless you count carpal tunnel syndrome or hurt feelings from particularly blunt code reviews. Regardless, a representative from an unfamiliar insurance company emailed, introduced herself, and instructed me to direct all claims related to this accident to her. On the surface, that seems straightforward, but I tripped several times throughout this process. When people learn I’m under workers’ compensation, they’re suddenly asking questions about lawyers and lawsuits. I’d assume that healthcare professionals would know and understand the nuances of short-term disability and workers’ compensation, but most don’t know even the broad strokes. I spoke to a workers’ compensation specialist from my health insurance company for direction for how to complete a form they’d mailed. The form asked for my lawsuit plans, which made no sense unless I could come out ahead by suing myself. The specialist had never heard about any relationship between short-term disability and workers’ compensation. I had to explain to her that my injury had nothing to do with work, and I’d been involuntarily lumped into workers’ compensation. The paperwork felt more onerous than the recovery.

While I was in the hospital, my wife had prepared our home for a geriatric invasion. In our family room sat a chair that went from fully reclined to fully erect at the push of a button, albeit a rather long push. I could sit down on it or stand up from it without engaging any core or leg muscles. A thick plastic seat with handles perched atop our master bathroom’s toilet, reducing the distance I’d have to sit to relieve myself. Finally, a plastic chair with grippy rubber feet stood in our master shower, allowing me to stand or sit while I washed, as my stamina dictated. All were welcome additions, although the toilet seat created some challenges. It stretched vertically about a foot and narrowed the bowl’s opening a few inches. It created, in effect, a sort of tunnel that all effluvia had to traverse, and the human body wasn’t designed to be so accurate in its ejections “down there.” Consequently, this chunk of plastic required more care and cleaning than either of us felt particularly comfortable with, and it was the first accommodation we retired. The moment I suspected I could navigate an unadorned toilet, the extra seat landed in the trash. The shower seat had a much longer run, and the chair still sits in our family room. Our dogs lounge on it when we’re not looking.

Two days after leaving the hospital, I could finally shower and remove my bandages. Water never felt so cleansing. The warmth. The purity. The sanitation. You don’t realize the luxury of a daily hot shower until you lose it. I’d had a few sponge baths in the hospital, but never a shower. I spent the next 15 minutes alternating between standing and sitting on the shower chair and feeling the glory of hot water. I scrubbed with shampoo and soap, and attacked the smears of medical tape adhesive that still clung to my side. By the end of my shower, I was exhausted but clean. I felt glorious. The adhesive resisted my scouring — I chipped away at it for another three weeks before it was completely gone.

I dried off in front of my bathroom sink and glimpsed the scar from my chest tube. I assumed I’d have a bit of a red slit curving along my rib cage — a gentle reminder of my drain ordeal. Instead, I saw the stuff of horror movies. Imagine a 1970s, overstuffed vinyl couch. You know the kind, with the buttons stitched to the back, creating crevices that collect dog hair and Ritz cracker crumbs? Now, imagine a button going missing but the stitches holding. That was my side: a deep, oozy gouge. The look was bad enough on a harvest gold couch, but on the side of a human body it’s downright nauseating. I later tested whether my scar was as disgusting as it seemed by walking around my house shirtless, and my children promptly gagged. If I were an underwear model, my career would have ended. Thankfully, over the next few weeks, my scar relaxed and faded. I now look more like a victim of a frustrated sculptor who, unable to get the rib curvature just right, placed his chisel between the ribs and gave it an angry whack. I’m not holding my breath, though, for a call from Calvin Klein.

I set a goal to return to work on January 2nd, which felt like more than enough recovery time. Again, I felt like I would use the time to read novels or learn new technologies, but again I wasn’t up to the rigor those activities demand. Nights and days blurred my routine; I’d often stare at the ceiling while owls hooted in the darkness outside our bedroom window, and sleep through the mid-afternoon while people arrived home from school or work. Still, I got out of bed every day, moving my body and getting my blood flowing. I’d awake and arise, always in slow motion, and shower. Then I’d swallow a protein shake and ease into my new recliner, leaning backward while standing and pushing the button to let it sit me down. I’d practice with the spirometer when my wife or mother reminded me. I’d take a nap, and then push the button again so the chair would stand me up, and I’d slog back to bed, where I’d watch TV. I managed to watch, for probably the third time, the entirety of the TV series The Office. Now, you may be saying, “Jolly good, old chap. Feeling chuffed, are you? That’s, what, 12 episodes, innit? Hardly a fortnight, methinks.” No, I didn’t watch the 12-episode UK version, though I’ve seen it before and find it lovely and charming enough. I watched the superior, American version of The Office. All 201 episodes. Besides, the UK version ought to be spelled The Ouffice, methinks. And the viewing went swimmingly until season three, episode 18, when Darryl negotiates a raise and Michael accidentally cross-dresses. When Michael walked to the window and I saw the cut of his suit, my laughter exploded, and my ribs protested. They weren’t ready. They creaked and shook, their splintered ends clattering against each other. I hugged myself, trying to quell the shaking, but that suit wouldn’t relent. Simultaneously laughing and crying, I enjoyed the moment as well as I could. And I focused on laughing while lying inert.

The doctors pegged my recovery at eight weeks. I never openly questioned that timeline, though I struggled to believe that first, you could so precisely predict how long it would take for my particular rib bones to knit, and second, that my spleen and lung would coordinate their own healing process with the ribs. Like, are they all on the same team? Or do the spleen and lung succumb to the ribs’ peer pressure? And why a round number of weeks? Couldn’t healing complete midweek? It seemed like something doctors say to not only keep patients in line, but also to preserve marriages: both partners know the official day healing will complete and normal activities will resume. You don’t have to debate or disagree on when you can carry a backpack or go to the gym. It’s a common goal. So I calculated the date I’d be all better: January 11. I would have circled the date in fat red marker, but we live digitally and no one looks at the lone paper calendar in our home anymore. Sadly, with my age, that meant that I kept forgetting the actual date, so I had to keep recalculating it. You’d think I’d have just set a reminder in my phone.